Integrated Marketing: Seeing the Big Picture

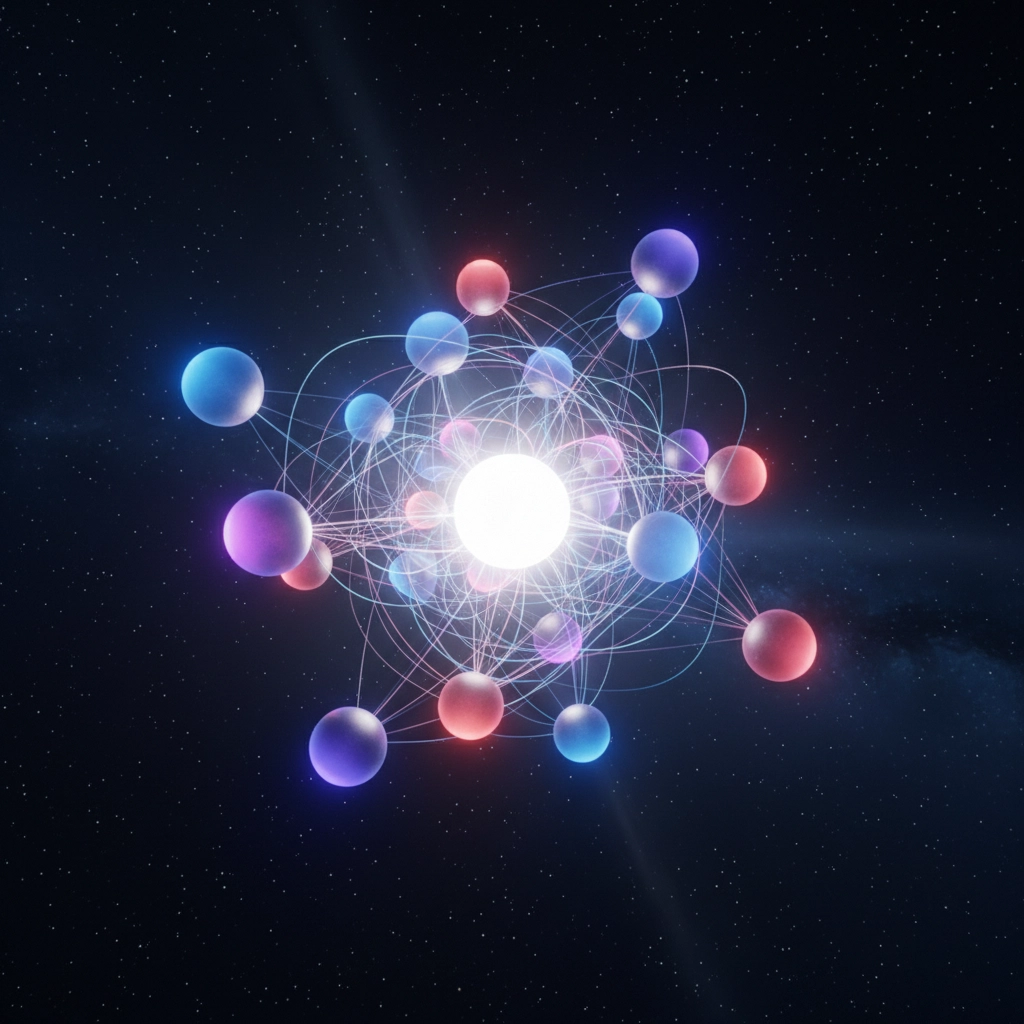

Marketing often feels like staring at individual stars in the night sky: each campaign, each channel, each tactic burning bright on its own. But step back far enough, and you start to see constellations. Patterns. A vast, interconnected system where every element influences the others.

This is integrated marketing: the art of seeing your entire marketing universe as one cohesive whole, rather than scattered fragments floating in digital space.

Beyond Isolated Planets

Most businesses approach marketing like they’re managing separate planets: each one spinning in its own orbit, rarely intersecting. Your social media lives on one world. Email campaigns exist on another. Your website floats somewhere else entirely.

This fragmented approach creates what astronomers call “dark matter”: the gaps between your marketing efforts where potential customers drift away, confused by mixed messages and disconnected experiences.

Integrated marketing recognizes that your audience doesn’t experience your brand in silos. They encounter your Instagram post in the morning, see your ad during lunch, and receive your email newsletter at night. To them, it’s all one continuous journey through your brand’s universe.

When these touchpoints align: when they orbit around the same gravitational center of consistent messaging and purpose: something powerful happens. Your marketing efforts amplify each other, creating a gravitational pull that draws customers deeper into your ecosystem.

The Gravitational Force of Consistency

In space, gravity isn’t just about individual objects: it’s about how mass and energy interact across vast distances. Your brand message works the same way. Every piece of content, every customer interaction, every marketing touchpoint either strengthens or weakens your gravitational field.

Consider how Apple’s marketing universe operates. Whether you encounter their products through a sleek commercial, a minimalist website, or a carefully designed retail space, you’re experiencing the same gravitational pull: the same emphasis on simplicity, innovation, and premium experience. Each touchpoint reinforces the others, creating a marketing system that’s far more powerful than the sum of its parts.

This consistency doesn’t mean everything looks identical. Just as planets in our solar system have unique characteristics while sharing the same sun, your marketing channels can have distinct personalities while orbiting around core brand values and messaging.

Mapping Your Marketing Constellation

Creating an integrated marketing strategy starts with understanding your current constellation. What marketing channels are you using? How do they connect? Where are the gaps in your customer’s journey through your brand universe?

Think of this as creating a star map. First, identify your marketing “stars”: your primary touchpoints with customers. These might include:

- Your website (often your brand’s sun: the central gravitational force)

- Social media platforms

- Email marketing

- Content marketing

- Paid advertising

- Direct sales interactions

Next, examine the space between these stars. How does someone move from discovering you on social media to becoming a customer? What happens after they make their first purchase? These pathways are your marketing constellations: the meaningful patterns that guide customers through your universe.

The goal isn’t to control every aspect of this journey, but to ensure that wherever customers encounter your brand, they’re receiving consistent signals about who you are and what you offer.

The Dark Energy of Disconnection

When marketing efforts aren’t integrated, you create what physicists might recognize as dark energy: a force that pushes elements apart rather than bringing them together. This shows up as:

- Conflicting messages across channels

- Customers who have to repeat information

- Marketing campaigns that compete with each other for attention

- Wasted resources on overlapping efforts

- Confused brand identity

This disconnection doesn’t just waste marketing budget: it actively repels potential customers. When someone sees a fun, casual social media post from your brand, then encounters a formal, corporate website, the cognitive dissonance creates friction. They start to question whether they understand what your brand really represents.

Creating Orbital Harmony

Successful integrated marketing creates what astronomers call orbital harmony: when different elements move in synchronized patterns that strengthen the entire system. This happens when you establish:

Consistent Brand Voice: Your communication style remains recognizable whether customers encounter you through email, social media, or face-to-face interaction.

Aligned Timing: Your campaigns work together rather than competing for attention. When you launch a new product, your social media, email, and advertising efforts coordinate to create momentum.

Shared Data: Information flows between your marketing channels. When someone downloads a resource from your website, your email system knows. When they engage with social media, your sales team can see the bigger picture.

Unified Goals: Instead of each channel optimizing for its own metrics, everything works toward broader business objectives.

The Expanding Universe of Opportunity

Just as our universe continues to expand, integrated marketing creates space for exponential growth. When your marketing channels work in harmony, they don’t just add to each other: they multiply each other’s effectiveness.

A customer might first encounter your brand through a thoughtful blog post that positions you as an expert. This builds trust. Later, they see a targeted social media ad that feels personally relevant because it builds on concepts from that blog post. The consistency reinforces their positive impression.

When they receive your email newsletter, it doesn’t feel like interruption: it feels like a continuation of an ongoing conversation. Each touchpoint builds on previous interactions, creating momentum that isolated campaigns could never achieve.

This compound effect explains why companies with strong integrated marketing strategies often see disproportionate results. They’re not just reaching more people: they’re creating deeper, more meaningful connections with the people they reach.

Navigating by Fixed Stars

In navigation, sailors use fixed stars as reference points to determine their position and plot their course. Your brand values serve the same function in integrated marketing. They provide the constant reference point around which all your marketing efforts can orient themselves.

When every team member, every campaign, every piece of content uses these core values as their North Star, integration happens naturally. You don’t need rigid oversight or detailed style guides for every possible scenario. Instead, you create a shared understanding of what your brand represents and trust your team to express that consistently across all channels.

This approach scales beautifully. As your marketing universe expands: new channels, new campaigns, new team members: the gravitational center holds everything together.

The Long View

From ground level, marketing often feels chaotic and overwhelming. There are so many channels to manage, so many metrics to track, so many tactical decisions to make every day. But step back to the cosmic perspective, and patterns emerge.

Integrated marketing isn’t about perfection: it’s about intentionality. It’s about recognizing that every marketing touchpoint exists within a larger system, and optimizing for the health of that whole system rather than just individual components.

When you approach marketing this way, something remarkable happens. Your efforts begin to compound. Your message becomes clearer. Your customers experience something more cohesive and compelling than any single campaign could create.

You stop managing isolated planets and start nurturing an entire universe: one where every element works in harmony to create something larger than itself.

The view from up here? It’s worth the perspective shift.

This post is grounded in the Space as Metaphor framework, which views space as “metaphor for method, moral orientation, and mode of transformation.” The framework helps us understand grant writing relationships not as transactional exchanges, but as sacred spaces requiring careful cultivation and ethical stewardship.

About Spaciology

Spaciology is not abstract theory; rather, it is a practice you can feel.

- Inside: Pause, breathe, notice.

- Outside: Design rooms, rituals, and agendas that slow the spin and invite care.

- Between us: Make dialogue a place where different truths can live together long enough to teach something.

Ultimately, leadership is the art of making space for what’s important (for everyone) and letting that clarity shape the next step. When we change the spaces from which we lead, our strategies change with them.

Spaciology Learning Commons

Want to go further? Join the Spaciology Learning Commons.

- Free membership gives you access to community conversations and introductory resources.

- Paid membership opens full access to courses, live sessions, and the complete Field Guide.